There is something basically wrong with the current adoption of Agile methods. The term Agile was abused, becoming the biggest ever hype in the history of software development, and generating a multi-million dollar industry of self-proclaimed Agile consultants and experts selling dubious certifications. People forgot the original Agile values and principles, and instead follow dogmatic processes with rigid rules and rituals.

There is something basically wrong with the current adoption of Agile methods. The term Agile was abused, becoming the biggest ever hype in the history of software development, and generating a multi-million dollar industry of self-proclaimed Agile consultants and experts selling dubious certifications. People forgot the original Agile values and principles, and instead follow dogmatic processes with rigid rules and rituals.

But the biggest sin of Agile consultants was to over-simplify the software development process and underestimate the real complexity of building software systems. Developers were convinced that the software design may naturally emerge from the implementation of simple user stories, that it will always be possible to pay the technical debt in the future, that constant refactoring is an effective way to produce high-quality code and that agility can be assured by following strictly an Agile process. We will discuss each one of these myths below.

Myth 1: Good design will emerge from the implementation of user stories

Agile development teams follow an incremental development approach, in which a small set of user stories is implemented in each iteration. The basic assumption is that a coherent system design will naturally emerge from these independent stories, requiring at most some refactoring to sort out the commonalities.

However, in practice the code does not have this tendency to self-organize. The laws governing the evolution of software systems are that of increasing entropy. When we add new functionality the system tends to become more complex. Thus, instead of hoping for the design to emerge, software evolution should be planned through a high-level architecture including extension mechanisms.

Myth 2: It will always be possible to pay the technical debt in the future

The metaphor of technical debt became a popular euphemism for bad code. The idea of incurring some debt appears much more reasonable than deliberately producing low-quality implementations. Developers are ready to accumulate technical debt because they believe they will be able to pay this debt in the future.

However, in practice it is not so easy to pay the technical debt. Bad code normally comes together with poor interfaces and inappropriate separation of concerns. The consequence is that other modules are built on top of the original technical debt, creating dependencies on the simplistic design decisions that should be temporary. When eventually someone decides to pay the technical debt, it is already too late: the fix became too expensive.

Myth 3: Constant refactoring is an effective way to produce code

Refactoring became a very popular activity in software development; after all it is always focused on improving the code. Techniques such as Test-Driven Development (TDD) allow refactoring to be performed at low risk, since the unit tests automatically indicate if some working logic has been broken by code changes.

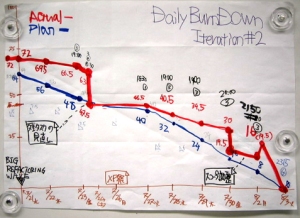

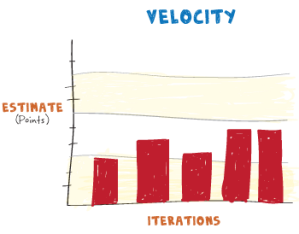

However, in practice refactoring is consuming an exaggerated amount of the efforts invested in software development. Some developers simply do not plan for change, in the belief that it will always be easy to refactor the system. The consequence is that some teams implement new features very fast in the first iterations, but at some point their work halts and they start spending most of their efforts in endless refactorings.

Myth 4: Agility can be assured by following an Agile process

One of the main goals of Agility is to be able to cope with change. We know that nowadays we must adapt to a reality in which system requirements may be modified unexpectedly, and Agile consultants claim that we may achieve change-resilience by adhering strictly to their well-defined processes.

However, in practice the process alone is not able to provide change-resilience. A software development team will only be able to address changing system requirements if the system was designed to be flexible and adaptable. If the original design did not take in consideration the issues of maintainability and extensibility, the developers will not succeed in incorporating changes, not matter how Agile is the development process.

Agile is Dead, Now What?

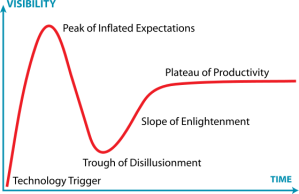

If we take a look at the hype chart below, it is sure that regarding Agile we are after the “peak of inflated expectations” and getting closer to the “trough of disillusionment”.

Several recent articles have proclaimed the end of the Agile hype. Dave Thomas wrote that “Agile is Dead”, and was immediately followed by an “Angry Developer Version”. Tim Ottinger wrote “I Want Agile Back”, but Bob Marshall replied that “I Don’t Want Agile Back”. Finally, what was inevitable just happened: “The Anti-Agile Manifesto”.

Now the question is: what will guide Agile through the “slope of enlightenment”?

In my personal opinion, we will have to go back to the basics: To all the wonderful design fundamentals that were being discussed in the 90’s: the SOLID principles of OOD, design patterns, software reuse, component-based software development. Only when we are able to incorporate these basic principles in our development process we will reach a true state of Agility, embracing change effectively.

Another question: what will be the next step in the evolution of software design?

In my opinion: Antifragility. But this is the subject for a future post…

What about you? Did you also experience the limitations of current Agile practices? Please share with us in the comments below.